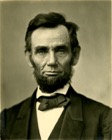

The Libraries of Famous Men: Abraham Lincoln

Sunday, August 13, 2017 - Filed in: General Interest

The eminent men of history were often voracious readers and their own philosophy represents a distillation of all the great works they fed into their minds. This series seeks to trace the stream of their thinking back to the source. For, as David Leach, a now retired business executive put it: “Don’t follow your mentors; follow your mentors’ mentors.”

While many of America’s presidents came from prominent, educated homes, one of our most famous — Abraham Lincoln — did not. Growing up in the backwoods of Kentucky and then Indiana, Lincoln rarely enjoyed the privilege of full-time schooling. His formal education, in his own words, came “by littles,” “did not amount to one year,” and was thoroughly “defective.”

And yet Honest Abe rose in society to become a shop owner, lawyer, and of course, President of the United States. How did he do this without much in the way of formal education?

He taught himself, becoming the consummate autodidact.

From traditional schoolboy texts like Nicholas Pike’s New and Complete System of Arithmetic and Thomas Dilworth’s New Guide to the English Tongue, to classic works we know today like Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and Robinson Crusoe, the young Lincoln read whatever he could get his hands on. He borrowed books from all his neighbors, until he could truthfully tell a friend that he had “read through every book he had ever heard of in that country, for a circuit of 50 miles.”

Lincoln would transcribe favorite quotes and passages from the works he read into a copybook, but he also committed reams of material to memory. This storehouse of literary and historical tidbits would come in handy throughout his life and impress those he met; he could recite a long poem at will, seemed to know the entire Bible by heart, and always had just the right story or analogy at his disposal to illustrate and explain his arguments.

This course of self-study naturally had to be squeezed into spare moments before, after, and between his daily chores and responsibilities. He would read until the last rays of the sun went down in summer, and until the embers in the fireplace failed to give off any light even in the faintest glow in winter. He kept a book in the crack of a log in the loft where he slept, so he could resume reading as soon as the dawn light broke. During the day, he always had a book with him, out of which to read snatches whenever he could. As a boy, his marked preference for “reading, scribbling, writing, ciphering, writing Poetry, etc.” over manual labor, led some of his family members to feel he was lazy. But when he entered his teen years, he became more committed to not indulging his studies until his chores were complete or he had earned a rest. So it was that he was often seen with both a book and an axe in his hands, and in this way he honed both body and mind as he grew into manhood.

When he was 23, Lincoln and a partner ran a small general store in New Salem, Illinois, a career that left young Abe with a good number of hours to read. Under the shade of a tree right outside the store’s entrance, he perused newspapers, studied scientific and philosophical texts, and developed a love for Shakespeare and the poetry of Robert Burns. He also began reading a complete edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, which he unexpectedly found at the bottom of a barrel he had purchased. These legal texts intrigued Lincoln; “The more I read,” he later recalled, “the more intensely interested I became. Never in my whole life was my mind so thoroughly absorbed. I read until I devoured them.” Lincoln’s studies would spur him to enter public life and to become a lawyer – a profession he mastered by his usual method – by teaching himself.

As Lincoln got older and became a politician, his reading regimen took a bit of a dip, but he continued to peruse books, giving each a chance. But if he did not find the work interesting or informative, he wasn’t against setting it aside. His tastes leaned decidedly towards non-fiction, once telling a friend: “It may seem somewhat strange to say, but I never read an entire novel in my life.” But even historical and scientific texts sometimes bored him, and he most enjoyed newspapers, shorter stories, and humorous prose.

While books did not always engage Lincoln, his appetite for poetry would remain undiminished throughout his life. As fellow attorney Milton Hay recalled, “The poets undoubtedly had their influence on Lincoln’s style and probably on his mind.” Scholar Douglas Wilson also notes Lincoln’s lasting affinity for poetry:

“one of the truly remarkable things about Lincoln as president is the extent to which he resorted to literature. Perhaps no president turned to English poetry while in office with the frequency that Lincoln did. He continued to recite his old favorites, such as ‘O Why Should the Spirit of Mortal Be Proud?’ or Holmes’ ‘The Last Leaf,’ their melancholy and brooding concern for human mortality having been rendered even more apt by the somber circumstances of civil war. And he read poets such as Thomas Hood to invoke the lighter side. But he repeatedly returned to Shakespeare.”

Shakespeare and Burns would remain Lincoln’s perennial favorites. Aide John Hay recalled that Abe “read Shakespeare more than all other writers together,” and it was said that Lincoln could quote Burns’ verse by the hour. Scholars David Harkness and R. Gerald McMurty posit the reason behind this fondness for the Scottish poet: “Born to poverty and obscurity, rising to heights of fame and popularity through long years of hard work, their lives present an interesting parallel. It is appropriate that Abe Lincoln should have found a kindred spirit in Bobby Burns, who spoke to his heart of the innermost yearnings, disappointments, and sorrows which both had experienced through similar backgrounds.”

Perhaps Lincoln turned to poetry, with its rhythmic, stirring, and sometimes haunting words, to cope with and understand his melancholic disposition. Rather than consume himself with tales of adventure (like Teddy Roosevelt was wont to do) it seemed that Abe needed to feel what he was reading, especially as he aged.

Below you’ll find a list of books that Abraham Lincoln read and enjoyed and learned from. The novels are mostly from his younger years, but as noted, he did peruse and skim through numerous books throughout his adult life. Take a page from our 16th president’s habits, and delve into the world of poetry; you’ll connect not only with Honest Abe, but perhaps your own inner depths as well.

Abraham Lincoln’s Reading List

Title, Author

Aesop’s Fables, Aesop

The Arabian Nights

Slavery, Discussed in Original Essays, Leonard Bacon

History of the U.S., George Bancroft

Editorials, Henry Ward Beecher

Bible

Commentaries on the Law, William Blackstone

The Pilgrim’s Progress, John Bunyan

Poems, Robert Burns

Poems, Lord Byron

Don Juan, Lord Byron

Elements of Character, Mary Chandler

Speeches, Henry Clay

Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe

A New Guide to the English Tongue, Thomas Dilworth

Journals and Debates of the Federal Constitution, Jonathan Elliot

Geometry, Euclid

Sociology for the South, George Fitzhugh

History of Illinois, Thomas Ford

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Franklin

Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Edward Gibbon

The Theory and Practice of Surveying Robert Gibson

Fanny, With Other Poems, Fitz-Greene Halleck

Poems, Oliver Wendell Holmes

Poems, Thomas Hood

Mormonism, John Hyde

Joe Miller’s Book of Jests, Joe Miller

Commentaries on American Law, James Kent

Poems, William Knox

Poems, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow

Complete Works, Edgar Allen Poe

Lives, Plutarch

Ancient History, Charles Rollins

An Authentic Narrative of the Loss of the American Brig Commerce, James Riley

Lessons in Elocution, William Scott

Complete Works, William Shakespeare

The Life of George Washington, Mason L. Weems

Liberty, John Stuart Mill

Analogy of Religion, Joseph Butler