Say Yes to Life: An Accessible Primer on Nietzsche’s Big Ideas

Monday, May 08, 2017 - Filed in: General Interest

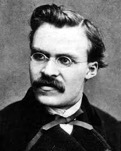

Friedrich Nietzsche introduced several ideas into Western philosophy that have had a huge influence on the culture of the 20th and 21st centuries. Existentialism, postmodernism, and poststructuralism have all been touched by Nietzsche’s work.

His impact isn’t just seen in academic philosophies, though, but also in the way many modern Westerners approach their lives. The love of struggle, the quest for autonomy and personal greatness, the clarion call of following your passion and making your life a work of art — these are all cultural currents Nietzsche helped shape and set in motion. Thus to really understand modern life in all its wonder, and weirdness, one must understand Nietzsche.

Below I highlight just a few of Nietzsche’s biggest and most intriguing ideas; even if you decide you vehemently disagree with them, they are excellent fodder for examining how you live and exist in the world. Do you, as Nietzsche exhorts, “say yes to life”? Or do you deny its powers and possibilities and simply loaf through your existence?

Keep in mind that this article isn’t an exhaustive look at Nietzsche’s work; it’s designed to be an accessible primer for those who wish to dip their toes into his philosophy. As such, I tried to simplify and condense the explanations as much as possible. For a more exhaustive and in-depth treatment, you’ll have to read the myriad books that have been written by Nietzsche and about his work; I’ll suggest some of the best to check out at the end.

Apollo and Dionysus

In Nietzsche’s first published work, The Birth of Tragedy, he describes two divergent outlooks embodied by the ancient Greeks: the Apollonian and the Dionysian. Together, Nietzsche argues, these two ethoses birthed one of the world’s most famous art forms — the Athenian tragedy.

Apollo was the sun god who brought light and rational clarity to the world. For Nietzsche, those who view things through an Apollonian lens see the world as orderly, rational, and bounded by definite borders. The Apollonian views humanity not as an amorphous whole, but as discrete and separate individuals. Sculpture and poetry were the arts best represented by the Apollonian ethos because they have clear structures and defined lines.

Dionysus was the god of wine, celebration, ritual madness, and festivity. Viewed through the Dionysian prism, the world is seen as chaotic, passionate, and free from boundaries. Instead of seeing humanity as being made up of atomized individuals, the Dionysian views humanity as a united, passionate, amorphous whole into which the self is absorbed. Music and dance, with their free-flowing forms, were the arts best represented by the Dionysian ethos.

For Nietzsche, the pre-Socratic Greek tragedies fused these two outlooks together perfectly. The works of Sophocles and Aeschylus forced the audience to answer one of life’s most burning questions: “How can human life be meaningful if human beings are subject to undeserving suffering and death?” The Apollonian answers this query by arguing that suffering brings forth a transformation — chaos can be turned into beauty and order. The Dionysian, on the other hand, contends that dynamism and chaos are not necessarily bad things. Simply being part of the chaotic flow of life and joyfully riding its waves was a beautiful and worthy pursuit in and of itself; any suffering that came along with the ride was simply the price of admission.

Nietzsche argued that after Socrates, tragedies began to emphasize the Apollonian ethos at the expense of the Dionysian. Instead of seeing tragedy as the natural result of living in a world of chaos and passion, the post-Socratic dramatists saw it as the consequence of some “tragic flaw” in a person’s character. Nietzsche believed this more “rationalized” view of tragedy extinguished some of life’s mystery and romanticism.

While this theory may seem very specific to a certain time, place, and art form, it has far wider implications. It’s important to have a basic understanding of the two concepts because they’re woven throughout the rest of Nietzsche’s work. For Nietzsche, the Dionysian perspective was the more life-affirming and vitality-spurring approach to life; consequently, he emphasizes it over the Apollonian.

Besides the Dionysian and Apollonian archetypes, Nietzsche looked to other Ancient Greek ideas to inform his worldview. He was particularly fond of the pre-Socratic Greeks and their Homeric warrior ethics. Strength, courage, boldness, and pride were virtues that Nietzsche championed throughout his life.

Perspectivism

“There are no facts, only interpretations,” Nietzsche famously wrote. From this, he is often accused of being a relativist, but a closer look at his work shows that this isn’t quite the case. Nietzsche doesn’t deny that there could be some big T Truth out there, but if there were, we would never be in a position to confirm its veracity because our observations are biased and “conceived within a language, within a culture, within a perspective, within the constraints and expectations of a theory.”

Instead of relativism, Nietzsche advocates for something that has been called “perspectivism.” Perspectivism in a nutshell means that every claim, belief, idea, or philosophy is tied to some perspective and that it’s impossible for humans to detach themselves from these lenses in order to suss out the objective Truth. Now, this may sound like relativism, but according to Nietzsche, it’s not the same thing. Unlike strict relativism, which says all views are equally valid because they’re relevant to each person, perspectivism doesn’t claim that all perspectives have equal value — some are in fact better than others. The job of the philosopher, according to Nietzsche, is to learn, adopt, and test as many different perspectives as possible to get a better picture of the Truth. This process may even require looking at the world with what appears to be opposing perspectives. While Nietzsche doesn’t think taking on different viewpoints can ultimately reveal the big T Truth (remember, it can never fully be unveiled because of our biases), he does feel it can get you pretty close to it.

As I read about Nietzsche’s perspectivism, I was struck by how similar it was to John Boyd’s OODA Loop. If you’ll remember, the OODA Loop is a methodology for making strategic decisions in the face of opposition — at least that’s how it’s often viewed in today’s business and military culture. For Boyd, though, the OODA Loop is more than just a decision cycle for military tacticians. It is a meta-paradigm for intellectual growth and evolution in an ever-shifting and uncertain landscape. The most important step in the OODA Loop is the Orient step, in which you constantly re-direct and re-frame your mind based on your observations of the world around you. Because our environment is always changing, we must always be orienting. A vital part of that is building a robust toolbox of mental models and testing out those mental models in the real world. According to Boyd, the more mental models one had at their disposal (even competing ones!), the more likely they were to understand the world and make good decisions. Sounds pretty much like Nietzsche’s perspectivism.

Master-Slave Morality

Nietzsche is perhaps most famous for his critiques and deconstruction of modern morality and religion. It is in Beyond Good and Evil and On the Genealogy of Morals that Nietzsche fleshes out this critique. An important element in Nietzsche’s criticism is the concept of “master morality” and “slave morality.” While Nietzsche presents the development of master-slave morality as a historical and anthropological reality, it’s better viewed as Nietzsche’s big picture psychological explanation for why we (we, as in all of humanity) have the morality that we do.

According to Nietzsche, morality began as “master morality.” He sees the aristocratic warrior values of the Homeric Greeks and other pre-Judeo-Christian cultures as the origin of true virtue. For them, the world wasn’t divided into “good” and “evil,” but rather “noble” and “ignoble.” To be noble meant successfully asserting your will on the world and getting what you wanted through your strength, courage, and excellence. Being noble meant being the best at whatever you did. This worldview required a hierarchical vision of humanity — some people were more excellent and noble than others. What’s more, there was no room for humility in this conception of nobility. As Nietzsche put it, “Egoism is the very essence of a noble soul.” If you did great things, you took responsibility for them and basked in the glory you received from your peers. The noble, or masters, were the ones who determined what was moral.

The ignoble, or “slaves” as Nietzsche called them, were the complete opposite of the noble. They were weak, timid, and pathetic. The ignoble couldn’t get what they wanted because they lacked the virtues of excellence and the ability to assert their will on the world. In fact, the ignoble avoided expressing their wants and desires because that could get them in trouble with the noble. They got along to get along. The noble did not esteem the slaves; they were at best pitied, at worst disdained.

Living a code based on the noble/ignoble dichotomy is what Nietzsche calls “master morality.” But, the philosopher argues, master morality only bred resentment in the slaves or lower classes. And it is this resentment that gave birth to “slave morality.” Slave morality, according to Nietzsche, was a “spiritual revenge” against the ruling class which sought to turn master morality on its head. Beginning with the Ancient Hebrews and continuing with Christianity, the ignoble or lower classes began to declare that the values of the master class were not only offensive to God, but that it was actually more righteous and excellent to be weak, humble, and submissive. Instead of splitting the world between the noble or ignoble, slave morality divided the world into good and evil. Under the rubric of slave morality, the noble man was seen as the evil man, and the ignoble man was seen as the good man. For Nietzsche, slave morality was a way to not just protect the weak, but to also exalt them.

What’s more, unlike master morality, which was created by the self-assertion of the noble individual himself and thus unique to him, slave morality was external and applied to everyone. Think the Ten Commandments.

While Nietzsche certainly praises master morality and casts slave morality in a bad light, he does see slave morality as serving an important psychological purpose in that it gave those without power a sense of self-esteem. The problem for Nietzsche is that, its dignity-bestowing properties aside, slave morality always puts its adherents in a secondary, dependent position. The slave can never have a sense of self-worth without thinking of someone else as evil; it’s reactive instead of proactive.

Nietzsche notes that it’s possible for an individual to be guided by both master and slave morality. Take the Pope for example. At one time in history, the Pope had actual political and military power. He governed nations and directed armies. He could, in a sense, be guided by master morality. But as a Christian, he followed a morality that emphasized humility and restraint. So there was a struggle between the two types of morality within a single man.

It’s not just popes who have to deal with this internal struggle; according to Nietzsche, we all do. What we call a bad or a guilty conscience is the result of our desire to live by a code of master morality butting against the pull of slave morality. We want to be rich and powerful, but we feel guilty for wanting those things because we’ve been told that the desire for wealth and power is evil. The battle between master and slave morality within ourselves also manifests itself when we feel bad about our successes or when we downplay them by providing self-deprecating excuses like, “Oh, it was just luck.” Slave morality for Nietzsche then becomes a sort of self-hatred.

Nietzsche argues that with the passage of time, slave morality overtook master morality and what we call morality today is almost entirely composed of the former’s values. Instead of seeking personal excellence, slave morality encourages us to judge and find fault in others so that we can say, “Well, at least I’m not as bad/evil/sinful as that guy.” It encourages us to paint our enemies in the worst possible light in order to feel justified in going after them; in the world of slave morality, there’s no room for the idea of the noble adversary. Slave morality also manifests itself in society’s overweening emphasis on humility; to even mention one’s accomplishments is seen as bragging. We balk at anyone who claims to be better than us. All in all, Nietzsche thought that living by the code of slave morality was a weak and pathetic way to go about life.

So if slave morality is so bad, what’s Nietzsche’s alternative? Interestingly, he doesn’t encourage us to go back to master morality because he feels we’re past the point of no return and it would be psychologically impossible to do so. Instead, Nietzsche argues that we must move “beyond good and evil,” and towards a morality that doesn’t depend on calling certain things bad in order for goodness to exist — a morality that’s proactive and not reactive, and focused on attaining personal excellence. According to Nietzsche scholar Robert Solomon, a type of Aristotelian virtue ethics would be a good candidate for this new (old) morality.

God is Dead

Of all the bold claims Nietzsche put forth in his life, none is more (in)famous than the idea that “God is dead.” Some have mistakenly interpreted this statement as Nietzsche celebrating the death of Deity. But a closer reading reveals a different story. Nietzsche was simply making explicit what had silently been happening in the West since the beginning of modernity. He was describing, not exulting. Instead of placing their faith in God and basing their worldview on a divine, universal law, most modern Westerners — even those who claimed to be devoted to their faith — conducted their lives and viewed the world through the Enlightenment-born prism of scientific materialism.

Rather than feeling that this evolution was something to celebrate, Nietzsche saw the death of God as tragic and traumatic. To get a sense of the travesty Nietzsche believed had happened in replacing God with science, read the following passage from The Gay Science in which Nietzsche has a madman announce that God is dead:

“Whither is God?” he cried; “I will tell you. We have killed him — you and I. All of us are his murderers. But how did we do this? How could we drink up the sea? Who gave us the sponge to wipe away the entire horizon? What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Whither is it moving now? Whither are we moving? Away from all sun? Are we not plunging continually? Backward, sideward, forward, in all directions? Is there still any up or down?… How shall we comfort ourselves, the murderers of all murderers? What was holiest and mightiest of all that the world has yet owned has bled to death under our knives: who will wipe this blood off us? What water is there for us to clean ourselves? What festivals of atonement, what sacred games shall we have to invent?

Nietzsche predicts that the death of God will bring with it the rejection of the belief in a universal moral law, which in turn will cause existential nihilism — a philosophy he detested. While Nietzsche didn’t think highly of “slave morality,” as we just discussed, he did think it was good for the psyche, and that religion played an important role in creating meaning — a center of gravity — in the world. Nietzsche predicted that once a universal basis of morality eroded away, “there will be wars the like of which have never been seen on earth before” — a prediction which came true not long after he died in 1900.

What often gets overlooked about Nietzsche’s pronouncement of God’s death is that he also points out that no one really noticed the Almighty’s passing. And why is that? First, even while Westerners put more and more of their faith in science and reason, they continued to profess a belief in God and kept up their religious practices. It’s not that people actively sought to prove the non-existence of God at the time, like today’s New Atheists. They simply started to ignore Him, even if they didn’t realize they were.

Second, Nietzsche argues that modern Westerners failed to notice the death of God because they continued to practice faith — just that now it was one centered on science and reason rather than the divine; if people were honest with themselves, Nietzsche would say, they would admit that they planned their days, made decisions, and picked careers based not on scripture and prayer, but on economic, sociological, and technological factors. While Nietzsche was an atheist and a fan of the scientific process, he believed this new faith in science wasn’t any better than the old faith in God. In fact, it was worse, for it made no room for a passionate, Dionysian spirituality that lent life vitality and meaning. What’s more, the reductivist explanations of scientific materialism promoted an empty, nihilistic outlook on the world.

Life-Affirming vs. Life-Denying

Nietzsche believed that joy required a man to love this mortal life right at this moment — with all of its ups and downs. “My formula for greatness in a human being,” Nietzsche argued, “is amor fati [literally, “love of fate,” the embracing of one’s fate]: that one wants nothing to be different, not forward, not backward, not in all eternity. Not merely bear what is necessary, still less conceal it … but love it.”

For Nietzsche, life itself, with all of its pleasures and pains, is what gives human existence meaning. Because struggles provide us a chance to test ourselves, we should not just welcome them, but love them, and love them dearly. The same goes for our enemies. We should respect and love our enemies, not out of piety, but because they challenge and push us. Nietzsche wants us to “say yes to life.” Rather than hide from it — embrace it head on. His idea of “eternal recurrence” (see below) really drives home this idea.

Life-denying philosophies are philosophies that attempt to downplay or even eliminate both the pains and pleasures of this life. For Nietzsche, the most pernicious type of life-denying philosophies are those that cause an individual to hold out for some “pie in the sky” future that will free them from all pain and sorrow. Instead of seeing mortality’s trials as something to struggle with and overcome, and in the process become stronger, life-denying philosophies encourage individuals to hate this life and look forward to another.

According to Nietzsche, Christianity and even scientific materialism promoted this sort of life-denying thinking. Christianity, Nietzsche argued, “was from the beginning, essentially and fundamentally, life’s nausea and disgust with life, merely concealed behind, masked by, dressed up as, faith in ‘another’ or ‘better’ life. Hatred of ‘the world,’ condemnations of the passions, fear of beauty and sensuality, a beyond invented the better to slander this life.”

Nietzsche saw scientific materialism as fomenting a similar dissatisfaction with life, by holding out hope not for heaven, but for a better future just over the horizon. Those who put their faith in science believe that through reason and innovation we’ll be able to overcome our physical limitations and become free from all suffering.

Nietzsche detested both of these views because both take a person’s focus off the vital present and direct it towards a distant future. Life, Nietzsche argued, had to be lived now.

The other type of life-denying philosophy Nietzsche criticized was asceticism. As a lover of the passionate Dionysus, Nietzsche believed that asceticism devalued the human passions by encouraging individuals to mortify and deny life’s vital energies. He felt that asceticism prevented people from enjoying all that mortality had to offer. Nietzsche’s critique of this philosophy as “life-denying” isn’t just directed towards religious practices like fasting, celibacy, or intense meditation. He also argued that the dogged pursuit of scientific knowledge was a form of asceticism as well, in that it caused a person to evade life — it’s hard to experience the fullness of mortality when you’re holed up in a laboratory or have your nose in a book all the time. Nietzsche also saw type-A workaholics who never have the time to enjoy the fruits of their labor as yet another category of life-denying ascetics.

Eternal Recurrence

An important doctrine (if you can call it that) buttressing Nietzsche’s life-affirming philosophy is that of “eternal recurrence” or “eternal return.” The idea is that time repeats itself over and over again with the same events. It’s not a new idea. Several ancient cultures had some conception of eternal recurrence, including the Persians, the Vedics of India, and the Ancient Greeks. Nietzsche simply expanded on the idea and used it as an existential test for modern man.

Nietzsche best captures his idea of eternal recurrence near the end of The Gay Science:

What, if some day or night a demon were to steal after you into your loneliest loneliness and say to you: “This life as you now live it and have lived it, you will have to live once more and innumerable times more; and there will be nothing new in it, but every pain and every joy and every thought and sigh and everything unutterably small or great in your life will have to return to you, all in the same succession and sequence — even this spider and this moonlight between the trees, and even this moment and I myself. The eternal hourglass of existence is turned upside down again and again, and you with it, speck of dust!” Would you not throw yourself down and gnash your teeth and curse the demon who spoke thus? Or have you once experienced a tremendous moment when you would have answered him: “You are a god and never have I heard anything more divine”?

If this thought gained possession of you, it would change you as you are, or perhaps crush you. The question in each and everything, “Do you desire this once more and innumerable times more?” would lie upon your actions as the greatest weight. Or how well disposed would you have to become to yourself and to life to crave nothing more fervently than this ultimate confirmation and seal?

Eternal recurrence is a thought experiment that serves as an existential gut check: Do you really love life?

People say they love their life all the time, but when they say that, they usually mean they love all the good things in life that happen to them. For Nietzsche, love of life requires loving all of life, even its pains and sorrows. For many, that’s a tough pill to swallow. If the thought of living your life over and over again fills you with dread, well, then according to Nietzsche, you don’t really love life.

So how does one come to love life? Nietzsche prescribes his philosophy of amor fati — the love of fate. Love and embrace all that life throws at you — both the good and the bad. Instead of resenting life’s trials, see them as opportunities to test yourself and grow.

Nietzsche had doubts about the human capacity for personal improvement (he was somewhat of a determinist; you were born the way you were, and pretty much stayed that way), but he does suggest that we can take action to create the kind of life we would gladly put on an infinite loop.

Does contemplating replaying your life fill you with feelings of anxiety and regret? Nietzsche would advise you to change course: Ask that girl out; write that novel; learn that new skill you’ve always wanted to learn; make amends with your estranged friend; head out on a long-dreamed of adventure. And at the same time, don’t despair over life’s hardships and uncertainties; ride them like a wave that takes you to a different, and even higher place.

Eternal recurrence would have a tremendous influence on the Existential philosophers of the 20th century. You can see it especially in Albert Camus’ essay “The Myth of Sisyphus.” The Existential psychologist Viktor Frankl echoed the idea of eternal recurrence in his book Man’s Search for Meaning when he writes: “So live as if you were living already for the second time and as if you had acted the first time as wrongly as you are about to act now!” In other words, live with no regrets!

To be clear, Nietzsche likely didn’t believe that we’d actually repeat our life over and over again. He did have some notes in which he tried to create a scientific proof of eternal recurrence, but it was deeply flawed, and he never published it. Nevertheless, for Nietzsche it doesn’t matter if eternal recurrence is an actual phenomenon — what matters is the motivating effect which comes from meditating on the idea.

Will to Power

Nietzsche first coined the phrase the “will to power” in his early aphoristic works as a response to Schopenhauer’s “will to life” philosophy. For Schopenhauer, all living creatures had a motivation for self-preservation and would do anything just to survive. Nietzsche thought this outlook was overly pessimistic and reactive. He felt there was more to life than merely avoiding death, and believed that living beings are motivated by the drive for power.

But what does Nietzsche mean by power? It’s hard to say. While Nietzsche used the phrase “will to power” throughout his published works, he never systematically explained what he meant by it. He just gives hints here and there. Many have interpreted it as the drive for control over others. While it could mean that, if we look at the original German phrase (Der Wille zur Macht), we discover that Nietzsche likely had something bigger and more spiritual in mind.

Macht means “power,” but it’s a power that’s more akin to personal strength, discipline, and assertiveness. With this in mind, many scholars believe that Nietzsche’s conception of the will to power is that of a psychological drive to assert oneself in the world — to be effective, leave a mark, become something better than you are right now, and express yourself. Exercising one’s will to power requires self-mastery and the development of personal strength by embracing struggle and challenge.

According to Nietzsche, this notion of will to power is much more proactive and even noble than Schopenhauer’s will to live. Humans are driven not just to survive, Nietzsche proclaims, but to dare mighty deeds.

Übermensch vs. The Last Man

In Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche introduced two archetypes of humanity: the Übermensch and the Last Man.

The Übermensch or Overman is an oft-misunderstood Nietzschean concept. Some have interpreted it as a biological, evolutionary goal — that through our mastery of technology and nature, humanity will be able to become a race of Supermen.

But that’s not what Nietzsche had in mind. He doesn’t think a person can actually become an Übermensch. Rather, the Übermensch is more of a spiritual goal or way of approaching life. The way of the Übermensch is filled with vitality, energy, risk-taking, and struggle. The Übermensch represents the drive to strive and live for something beyond oneself while simultaneously remaining true and grounded in earthly life (no other-worldly longings in Nietzsche’s world). It’s a challenge to be creators and not mere consumers. In short, the Übermensch is the full manifestation of the will to power.

Nietzsche never states what exactly we should be striving for that’s beyond ourselves or what we should be creating. That’s for each man to figure out for themselves. It could be a work of art, a book, a business, a piece of legislation, or a strong family culture. Through the act of creation, we can forge a legacy that lives beyond our mortal life. By seeking to live as the Übermensch, we can attain immortality in a this-worldly sense.

Contrast the Übermensch with the Last Man. The Last Man is the very antithesis of a Superman:

Lo! I show you THE LAST MAN.

“What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?” — so asketh the last man and blinketh. The earth hath then become small, and on it there hoppeth the last man who maketh everything small. His species is ineradicable like that of the ground-flea; the last man liveth longest. “We have discovered happiness” — say the last men, and blink thereby. They have left the regions where it is hard to live; for they need warmth. One still loveth one’s neighbor and rubbeth against him; for one needeth warmth.

Turning ill and being distrustful, they consider sinful: they walk warily. He is a fool who still stumbleth over stones or men! A little poison now and then: that maketh pleasant dreams. And much poison at last for a pleasant death. One still worketh, for work is a pastime. But one is careful lest the pastime should hurt one. One no longer becometh poor or rich; both are too burdensome. Who still wanteth to rule? Who still wanteth to obey? Both are too burdensome. No shepherd, and one herd! Everyone wanteth the same; every one is equal: he who hath other sentiments goeth voluntarily into the madhouse.

They have their little pleasures for the day, and their little pleasures for the night, but they have a regard for health. “We have discovered happiness,” — say the last men, and blink thereby.

The Last Man plays it small and safe. He blinks and misses life’s energies. There is no ambition, no risk-taking, and no vitality in the Last Man. He avoids challenges because challenges result in discomfort. The Last Man doesn’t want to create or be a leader because creation and leadership are “burdensome.” There is no desire to live for something beyond himself. The Last Man “has discovered happiness” in his “little pleasures” and just wants to be left alone so that he can live a long, unremarkable life. The Last Man is simply surviving, and not truly living. In the words of Robert Solomon, the Last Man is the “ultimate couch potato.”

While Nietzsche didn’t think it possible to transform oneself into a full-on Übermensch, the Last Man represented a decidedly attainable state. Look around you and even at yourself. You’ve likely seen glimpses of the Last Man within yourself; he serves as a warning of what you’ll become if you cease striving for things beyond yourself — if you don’t nurture the flashes you sometimes also get of your superhuman potential.

Become Who You Are

A favourite directive of Nietzsche’s to his readers is one he borrowed from the ancient Greek poet Pindar: “Become who you are.” But what exactly does this exhortation mean?

For Nietzsche, becoming who you are doesn’t mean becoming who you want to be. That can only lead to frustration.

For example, I would love to be an NFL player, but I’m 32 years old, haven’t played football in 17 years, and wasn’t blessed with natural athleticism. Professional football isn’t and never was in the picture for me.

Rather, the mandate to “become who you are” requires us to acknowledge the limitations that biology, culture, and even blind luck have placed on us. Within these limitations, we must strive to live our natural talents and abilities to the fullest extent possible. In fact, we should embrace our limitations because they provide us the opportunity to exercise more creative power than if we had complete freedom. In a way, Nietzsche’s notion of “becoming who you are” is akin to a haiku. The constraints of haiku poetry force the poet to think deeply about which words to use and how to structure his prose. The constraints counterintuitively encourage creativity.

Thus, “become who you are” requires you to love fate, to relish the cards life has dealt you — even if it’s a terrible hand — and do the best you can with them. “Become who you are” is a mandate to exercise creative power and become the author your life. This notion of self-realization helps you avoid the feelings of resentment and angst that come when you wish for a life that simply doesn’t and can’t exist. Instead, Nietzsche argues, we should channel our energies into focusing on the here and now and find joy in the journey.

Conclusion

I hope this two-part series has given you a clearer understanding of the basics of Nietzsche’s famous philosophy. Regardless of your beliefs and background, grappling with Nietzsche’s ideas can give you insight about how you want to live your life, as well as the why behind how many others live in the modern West.

If you’re a theist, Nietzsche’s diagnosis of the death of God serves as a spiritual gut check, forcing you to ask yourself, “Do I really live my life as if there is a God? If I really believed without a doubt that the claims of my faith are true, how would my daily behavior, how I spend my time, and my life goals change?” He also causes you to reflect on whether you’re enjoying this earthly existence, in all its wonder, or simply pining for the next world; do you see life as something to be enjoyed, or simply endured?

If you’re an atheist, Nietzsche challenges you to not simply replace your faith with science, which can ultimately lead to nihilism, but to actively seek a vital spiritual life filled with meaning.

For Nietzsche, the challenge for all modern men is to create and live by their own life-affirming values — to become autonomous — and to find meaning in a world that has become void of any such thing. In the present age we often feel like we are “straying as through an infinite nothing”; Nietzsche’s exhortation to all is to fight against this empty drift, to become who you are, to love suffering and challenge as much as ease and comfort, and to always, always say yes to life.