Trade Deficits and the Investment Balancing Act

Sunday, April 13, 2025 - Filed in: General Interest

Not quite.

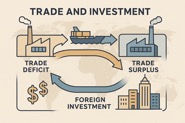

What many people don’t realize is that trade and investment are two sides of the same coin. Trying to “fix” one without understanding the other can backfire—badly.

Let’s break it down.

What Is a Trade Deficit, Really?

Imagine your household spends $1,200 a month but only earns $1,000. That’s a $200 deficit. To keep going, you either dip into savings or borrow money.

Countries are similar. When the United States imports more than it exports, it runs a trade deficit. That means more money flows out to buy foreign goods than flows in from selling American goods abroad.

But that money doesn’t just disappear—it comes back in another form.

⸻

The Flip Side: Investment Flows

The dollars other countries earn from selling goods to the U.S. often get recycled back into the U.S. economy as investment.

Take China. It sells billions of dollars’ worth of products to America—everything from electronics to toys. With the surplus dollars it earns, China buys U.S. government bonds, invests in real estate, and sometimes even buys into American companies.

Why? Because the U.S. is still one of the safest and most attractive places in the world to invest.

So here’s the key point:

The U.S. can only run a trade deficit because it is also receiving investment from abroad.

Just like your household could keep spending more than it earns—as long as someone is lending you money or investing in your business.

⸻

The Balancing Act

Every country’s international finances must balance:

• If you run a trade deficit, you must run a capital surplus (i.e., bring in foreign investment).

• If you run a trade surplus, you’re likely investing your profits abroad.

These two flows—trade and capital—balance out in what’s called the balance of payments.

So when U.S. leaders say, “We need to shrink the trade deficit with China,” what they’re really saying is, “We want to buy fewer Chinese goods.” But here’s the risk:

If the U.S. buys less from China, China earns fewer dollars—and has less reason to invest in the U.S.

That’s not just abstract theory. It has real-world consequences.

⸻

What Could Go Wrong?

If China reduces its investment in the U.S.:

• The U.S. government may struggle to borrow at current low interest rates.

• Mortgage rates could rise.

• The U.S. dollar might weaken.

• Financial markets could become unstable if foreign capital dries up too quickly.

In other words, the trade war could become a capital war—and that’s much harder to fight.

⸻

A Simple Example

Let’s say Ted’s Tools (your business) buys parts from a supplier in China. Every month, you send them $10,000. That’s a trade deficit for you.

But the supplier then reinvests that money by buying shares in your company or lending you money to grow. Everyone wins—so long as trust and cooperation continue.

Now imagine you say, “I’m tired of running a deficit,” and stop buying from them. The supplier loses income, so they stop investing. Now you’re short on parts and short on cash. That’s the danger at the global level too.

⸻

Final Thoughts

It’s tempting to think we can just “rebalance trade” by cutting imports or imposing tariffs. But unless we also cut spending, boost savings, or become a bigger magnet for domestic investment, the money has to come from somewhere.

Trade deficits aren’t just about buying too much—they’re also about being a safe place for others to invest.

Disrupting that balance without a broader strategy risks unintended—and potentially damaging—consequences.

⸻

Want to Learn More?

Next time you hear about trade deficits or tariffs, think about what’s happening on the other side of the ledger. It’s not just about what we’re buying—it’s also about who’s investing in us, and why.

⸻

Coming Up Next…

In the next post, we’ll take a closer look at how Germany, Japan, and Canada manage the same global rules of trade and investment—often with vastly different results. What lessons can we learn from countries that run surpluses but still keep investment flowing?

Hint: It’s not just about the goods—they’ve learned how to manage their savings, productivity, and capital in ways the U.S. has not.